It looks like the northern U.S. might have a cold fall this year 🥶

How do we know? Because sea surface temperatures in the Pacific have been cooling, pointing to a 71% chance of La Niña conditions forming.

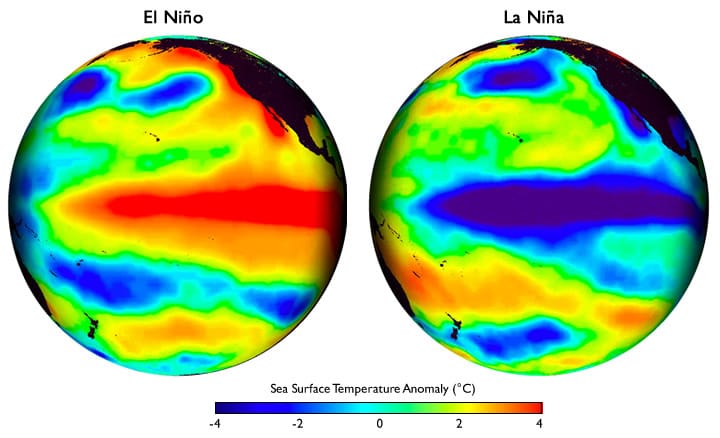

La Niña is a climate phenomenon involving unusually cool surface waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. When these conditions take hold, they often bring colder weather to the northern U.S., meaning more demand for heating and higher energy use.

Just as important, it rules out the possibility of an El Niño, the warmer counterpart, which tends to bring milder weather, wetter conditions in the Southern U.S., and different energy demand patterns.

The Pacific Ocean sea surface temperature during El Niño and La Niña episodes. Image from Climate.gov.

These ocean-driven weather patterns also shape how much energy can be produced from renewables:

⛅ Cloudier skies cut into solar generation, leaving those with rooftop systems more dependent on the grid.

🌬️ Stronger winds give a boost to wind power, helping to stabilize supply and even lower prices at certain times.

🏭 But wetter conditions can disrupt coal production, with swings in heating and cooling demand adding more pressure to the system.

⚡ The result is a more unpredictable energy mix, with the potential for supply crunches and sudden price swings if extreme weather hits.

This is a U.S. example, but the same principle plays out globally. Ocean data drives weather forecasts that guide decisions across industries like energy markets, shipping routes, fisheries, offshore wind, retail and insurance.

Energy markets, worth trillions globally, are one piece of the puzzle I’d like to highlight. It matters because the prices set there are baked into the global economy in ways most people never see.

A gas trader adjusting futures (agreements to buy or sell gas at a set price later) based on weather forecasts can ultimately influence how much families pay to heat their homes or how affordable everyday essentials like cooking fuel and electricity are.

The forecasts used come from global models that pull in data from satellites, ocean buoys, and sensor networks. Private companies then refine those models to provide sharper insights.

How good are these insights? Only short-term forecasts up to about a week are strong. Uncertainty grows the further ahead you look, especially in regions with fewer sensors.

Smarter AI-driven models, denser ocean sensor networks, and better data integration can help.

Several startups are already working on this, one of them is Planette. They’re an AI and science-driven startup providing environmental forecasts up to one year ahead. Ocean data plays a critical role in these forecasts.

As the Planette CEO & Co-founder, Hansi Singh, put it in our conversation, “Long-range weather forecasts are only possible because of the ocean, it has a much longer memory than the atmosphere, so we can predict beyond the traditional 7-day weather forecast window.”

It’s important to note that long-range forecasts don’t predict the weather on a given day, they reveal predictive patterns, like a warmer winter ahead or a higher chance of drought.

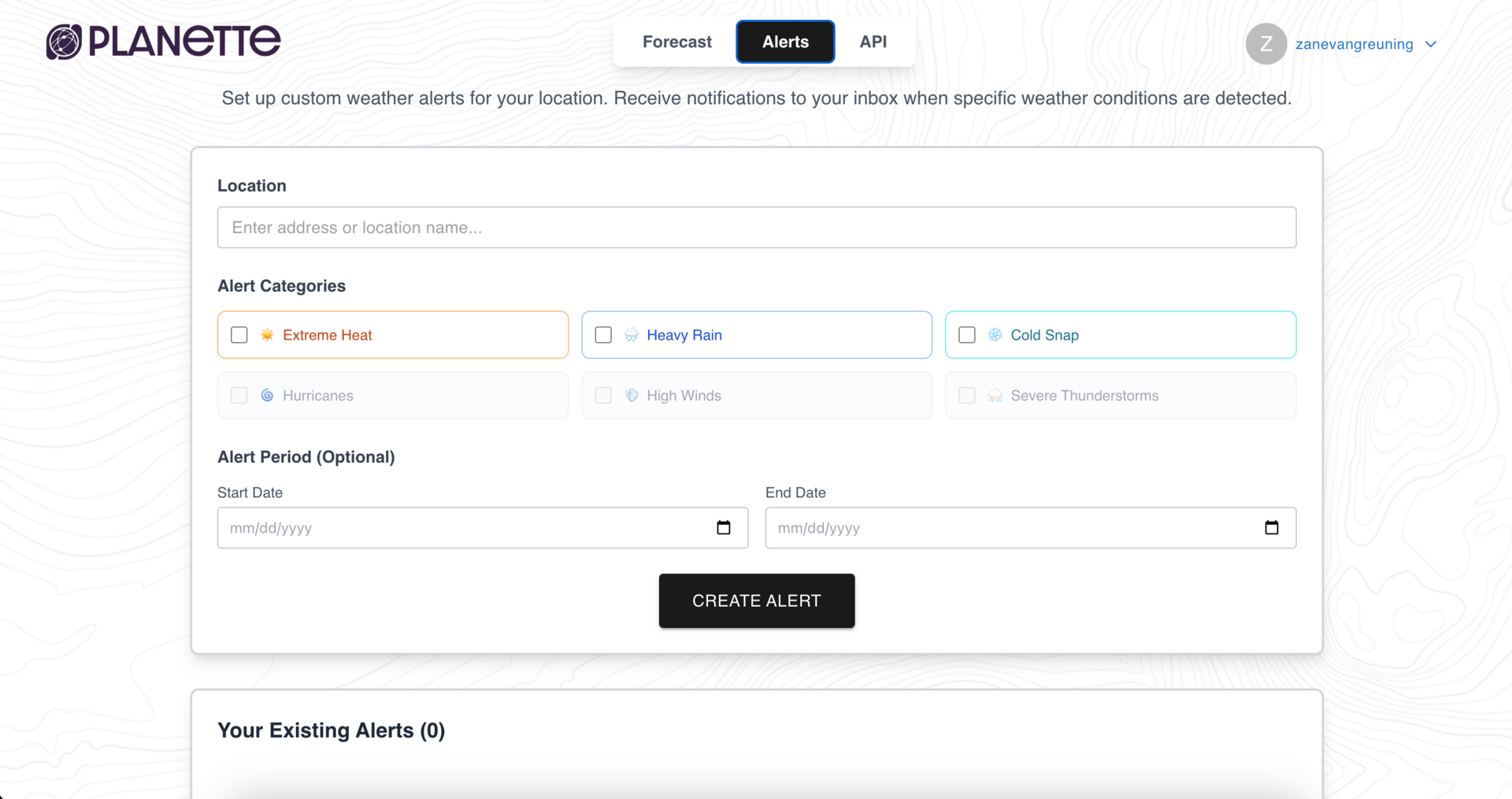

Planette dashboard showing weather alerts you could set up for your region.

With long-range forecasting usability matters as much as accuracy. By turning the ocean’s signals into accessible insights, companies like Planette show how ocean intelligence can aid different industries and shape daily life.

It can help fisheries plan their seasons, utilities balance supply, traders set fairer prices, and households avoid the worst of sudden spikes.

Planette hosts a weekly series on long-range environmental forecasts that’s worth following: https://www.planette.ai/events.

Thank you for reading the second edition of Blue Tide! If you have any topics or companies you’d enjoy reading about then please reach out.

🦑 Zané